| Author |

Message |

kola@aalbc.com

Moderator

Username: Kola

Post Number: 546

Registered: 02-2005

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Sunday, April 17, 2005 - 04:43 pm: |

|

You all know how much I was inspired by my childhood hero ALICE WALKER.....the writer who gave us "THE COLOR PURPLE", created the terms "womanist", "colorism" and who has written the best books ever written about Female Genital Circumcision (a condition that afflicts me).

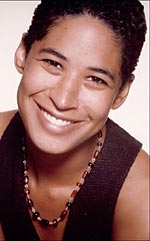

Well, Alice has a beautiful and gifted daughter named who's also a writer, REBECCA WALKER, and she has a BLOG!

http://www.rebeccawalker.com/blog/index.htm

I so admit that as much I love Alice Walker, and feel as though her work has mentored me, I really have not been able to relate to REBECCA WALKER or to be interested in much of what she writes or says----but I do hear that her book about being Bi-racial was absolutely astounding.

She also has a web site:

http://www.rebeccawalker.com/index.html

|

kola@aalbc.com

Moderator

Username: Kola

Post Number: 547

Registered: 02-2005

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Sunday, April 17, 2005 - 04:48 pm: |

|

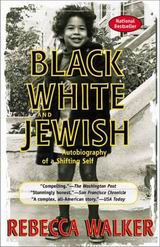

Publishers Weekly Review

The daughter of famed African American writer Alice Walker and liberal Jewish lawyer Mel Leventhal brings a frank, spare style and detail-rich memories the this compelling contribution to the growing subgenre of memoirs by biracial authors about life in a race-obsessed society. Walker examines her early years in Mississippi as the loved, pampered child of parents active in the Civil Rights movement in the bloody heart of the segregated South. Torn apart by the demands of their separate careers, her parents' union eventually lost steam and failed, leaving Walker to shuttle back and forth across country to spend time with them both. Deeply analytical and reflective, she assumes the resonant voices of an inquisitive child, a highly sensitive teen and finally a young woman who is confronted with the harsh color prejudices of her friends, teachers and families-both black and Jewish-and who tires desperately to make sense of rigid cultural boundaries for which she was never fully prepared by her parents. Whether she's commenting on a white ballet teacher who doubts she'll ever be good because her black butt's too big, Jewish relatives who treat her like an alien, or a boyfriend who feels she's not black enough, Walker uses the same elegant, discreet candor she brings to her discussion of her mother and the development of her free-spirited sexuality. Her artfulness in baring her psyche, spirit and sexuality will attract a wealth of deserved praise. (Jan. 2) Forecast: Coming the heels of her mother's story collection, The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart (which offers a fictional treatment of Alice Walker's marriage to Leventhal), this literary debut by the younger Walker, who has been recognized by Time as one of her generation's leaders, is destined to generate excitement. Although Walker is likely to be compared to Lisa Jones (the daughter of Amiri Baraka and Jewish writer Hetty Jones), who tackled the myth of tragic mulatto in Bullet Proof Diva (1995), a collection of columns from the Village Voice, Walker's higher profile and narrative treatment of these themes will draw a wider audience who no doubt will greet her warmly on her 10-city tour.

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Booklist Review

When Alice Walker and Mel Leventhal married, their love was an illegal but idealistic leap of faith. But "Black Power" replaced "Integration" as the civil rights movement's slogan; a few years later, Walker and Leventhal divorced. Their daughter, Rebecca, shuttled back and forth, spending two years with her writer mom on the West Coast, then two in the East with her civil rights lawyer dad and his new family, then back again. Identity is an issue for every kid, but for Rebecca, it was especially challenging; she was too black for one East Coast boyfriend, not black enough for the tough girls in her San Francisco school. (In New York, at one point, she hung with Puerto Rican kids, because they seemed more welcoming than either blacks or whites.) Both families gave Rebecca a good deal of freedom early--too much, some readers will no doubt feel. Happily, the author ultimately found teachers who encouraged her to build her identity around her capacities rather than her bloodlines, and her capacities are reflected in this involving, honest, poignant memoir.

By Mary Carroll

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

|

kola@aalbc.com

Moderator

Username: Kola

Post Number: 548

Registered: 02-2005

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Sunday, April 17, 2005 - 05:50 pm: |

|

This essay is magnificent.

BEING RAISED BY ALICE WALKER

by Margo Hammond, © The New York Observer, Feb 5, 2001

____________

"Are you really black and Jewish?" a fellow Yalie once asked Rebecca Walker. "How can that be possible?" She didn't answer him, but the question was one she had been asking her whole life: "Am I possible?"

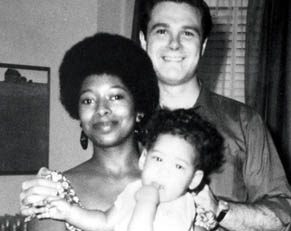

Her mother, writer Alice Walker, and her father, Jewish civil rights lawyer Mel Levanthal, certainly must have thought so when they posed for their wedding portrait in 1967, in defiance of Mississippi's miscegenation laws. Didn't their "shiny, outlaw love," as their daughter calls it, herald the racial harmony we all knew was just around the corner? Wasn't racial animosity, after all, just a giant misunderstanding that could be remedied by the "clean application of Law," as Mel Levanthal believed, or through the "magic ability of words to redefine and create subjectivity," as per Alice Walker?

History, of course, proved such idealism a bit premature. Racial differences, like marriage itself, turned out to be more complicated. With the rise of black nationalism, Mr. Levanthal was recast almost overnight as an interloper by the very people for whose rights he had fought. Ms. Walker left her husband's arms to embrace feminism and eventual Color Purple fame. While Ms. Walker made San Francisco her home, Mr. Levanthal ended up in lily-white Larchmont, N.Y. , married to the nice Jewish girl his parents had preferred all along. These new worlds barely intersected. Except for one small matter: a "copper-colored" daughter.

"The only problem, of course, is me," Rebecca Walker writes (always in the present tense), describing her parents' union and breakup in Black, White and Jewish. After black and white have retreated to their own comfort zones, "I no longer make sense. I am a remnant, a throwaway, a painful reminder of a happier and more optimistic but ultimately unsustainable time."

That, of course, could be the lament of many a child of divorce-race is only part of the story here. In this lyrical and devastatingly honest memoir, Rebecca Walker bravely shares the details of childhood agonies associated with mixed heritage. There's her Jewish great-grandmother's stony silence; there's her black uncle who described her laugh as "cracker." But how much of Rebecca's personal pain came from being crushed between two (or perhaps three) estranged cultures? How to separate the racial wheat from the general human emotional chaff? How much can be blamed on those other usual suspects: adolescent angst, cultural ennui and that ubiquitous American devil, bad parenting?

Rebecca Levanthal Walker (nee Rebecca Grant Levanthal) was in the third grade in Brooklyn when her parents separated. When Alice Walker moved to San Francisco, "where she feels she can write better because she can see the sky," Alice and Mel decided on a joint custody agreement: They shuttled their young daughter back and forth between the East and West coasts every two years.

What were they thinking? "I don't know how they come up with that number, two, as opposed to one, or why they didn't simply put me in junior high here and high school there," Rebecca writes with admirable restraint. "I don't know if staying in one city so that I wouldn't have to spend my life zigzagging the country, so that I could have some semblance of a normal relationship with friends and family members, ever crossed either of my parents' minds."

Trapped in a destructive cycle, needing to re-invent herself every couple of years (and having had little clue as to who she was in the first place), Rebecca found she belonged simultaneously to two worlds and to none. Not surprisingly, some of the adjustments she made took on a racial twist: Denying part of herself each time she shuffled from city to city, from Jewish to black, from status-quo middle class to radical-artist bohe-mian, she trained herself to keep the code, not to say anything too white when she was with friends from the inner city, not to say anything too black when she was at Jewish summer camp.

But mostly Rebecca Walker's story, as she tells it, is about raising herself. Her mother bragged in interviews that she and her daughter were like sisters, but as Rebecca points out, "being my mother's sister doesn't allow me to be her daughter." So while Alice Walker was off on speaking engagements, sometimes for days on end, her "sister" Rebecca was choosing her own high school, taking drugs, having sex and generally fending for herself. When, at 14, Rebecca told her mother she was pregnant, Alice Walker arranged for an abortion. "She doesn't lecture me, she doesn't say, How did this happen, aren't you using birth control, she doesn't say much of any thing, except to call her boyfriend a few hours later and tell him .... I hear her sighing as she speaks, the same sigh I hear when she worries about money, when she's feeling overwhelmed and retreats to her bedroom for hours, sometimes days," Rebecca writes.

When it was Rebecca's father's turn to parent, he didn't do much better. He and stepmother Judy, whom Rebecca guiltily called "Mom," had little or no idea about Rebecca's complicated life. Perhaps afraid of the answers, they didn't ask any questions. "They don't ask if I'm having sex or giving blow jobs or feeling safe," writes Rebecca. When she was in 12th grade, she legally changed her name to Walker, a name that "links me tangibly and forever with blackness." Her father, "oblivious to my reality," suggested her choice had something to do with anti-Semitism.

To judge from Rebecca's account, Alice Walker and Mel Levanthal stumbled into an irony of their own making. They were certain that understanding across racial lines was possible, but as parents they failed to realize that their daughter's unique racial experiences effectively placed her in a "race" to which neither of them belonged.

Rebecca survived. Though she doesn't write much about her present life, we learn in passing that she works as a political activist in the San Francisco Bay area, and that she's gay. She makes it clear that she has found her own way at last. When her female companion, who is black, asks her if she considers black people her people, Rebecca Walker responds with impressive clarity: How can she feel fully identified with any one group of people when she has other people, too, who are not included in that grouping?

Black, White and Jewish should make Rebecca's parents squirm, but it's hardly a Mommy and Daddy Dearest. el and Alice are no different from legions of other baby-boomer parents who have mixed a high degree of self-absorption with an even higher degree of creative idealism. Even when parents fall short of their own ideals, they can still manage to pass something of value on to their children. Despite all their parental bumblings, Alice and Mel gave their daughter the tools she needed to work her way out of all this confusion, not the least important of which was love.

|

Yvette Perry

"Cyniquian" Level Poster

Username: Yvettep

Post Number: 118

Registered: 01-2005

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Friday, April 22, 2005 - 08:24 am: |

|

This is great, Kola. Thanks. |

kola@aalbc.com

Moderator

Username: Kola

Post Number: 559

Registered: 02-2005

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Friday, April 22, 2005 - 11:35 am: |

|

Hi Yvette.

I also just finished reading Rebecca's book "BLACK, WHITE and JEWISH".....

....it's one of the best autobiographies I have EVER read.

She's such a fabulous writer and she's so stunningly honest. I love her (although I'm jealous she gets to be Alice's daughter----which was one of my childhood fantasies. LOL. The book does burst that whole bubble about "etheral, angelic" Alice).

|

|