| Author |

Message |

Tonya

AALBC .com Platinum Poster

Username: Tonya

Post Number: 4456

Registered: 07-2006

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Wednesday, February 14, 2007 - 06:38 pm: |

|

Diary of a mad businessman

Bringing urban theater to the screen has made Tyler Perry a star in Hollywood. Fortune's Nadira A. Hira reports.

By Nadira A. Hira, Fortune writer-reporter

February 14 2007: 5:21 AM EST

(Fortune Magazine) -- Los Angeles is looking fabulous today. It's a November afternoon - bright, clear skies, sparkling ocean - and from this glass mansion in the Hollywood Hills, a flock of seagulls can be seen taking to the air. And the cinematic cliché doesn't end there.

Cut to the interior, and the house is all hard lines and mute colors - abstract art adorns the walls, low chrome tables showcase tall, skinny vases and the modern gray couches are so low that they appear only marginally preferable to the floor for the dozen actors and actresses composing the tableau.

Add the sound, though, and everything changes. Tyler Perry, the writer-director-producer-actor-composer who began his career as a playwright, is fielding reactions to the recent table reading of his next film, "Why Did I Get Married?"

Far from an orderly roundtable of notes and nods, the debate among the actors - who range from black Hollywood notables to neophytes handpicked by Perry - is heated, personal, familial. "Marriage is a choice, not a feeling," Tracee Ellis Ross, star of the sitcom "Girlfriends," declares. A male actor - whose identity we'll conceal for his own protection - weighs in: "Cheating is physical, athletic, like dunking."

Perry listens, brow furrowed, his 6-foot-6 frame spilling out of his armchair. He has invited the actors here to talk to him about marriage, but before long they are all looking at him expectantly. "I'm not getting married," he says with a coy smile. "I need someone who can just get in the water and not disturb it too much."

"That's not a woman, honey," Ross retorts. "That's a piece of paper."

The conversation sounds more like a church coffee hour than an L.A. brainstorming session, and it could come straight out of one of Perry's wildly successful dramas.

Perry, 37, is building a maverick media company by translating "urban theater" - the often melodramatic, revival-style stage plays that tour the country catering to black audiences - into mainstream movies and television shows. It's a niche he has come to dominate so thoroughly that he is able to do things in Hollywood that most others - especially newcomers - simply can't.

An impressive résumé

In September, Perry opened Tyler Perry Studios in Atlanta, one of the first movie studios in this country owned by an African American. He made his first two films - 2005's "Diary of a Mad Black Woman" and 2006's "Madea's Family Reunion" - with Lions Gate Entertainment for a total of just $11 million. They both opened at No. 1, and together they grossed over $110 million, shocking Hollywood with their profit margins. His third movie, this month's "Daddy's Little Girls," is opening with similar projections.

Since 1998 his 11 touring stage plays have brought in over $150 million. And DVDs of the movies and plays have sold more than 11 million copies. He even took the top spot on The New York Times nonfiction bestseller list with the publication in 2006 of "Don't Make a Black Woman Take Off Her Earrings: Madea's Uninhibited Commentaries on Love and Life," written in the voice of Madea, the over-the-top grandma he's played in his films and many of his plays.

Remarkably, Perry has retained ownership of all his work. In a business where a cardinal rule is to use other people's money, he has used his own to create a library of substantial and growing value.

But perhaps his most surprising feat has occurred on the small screen. Last fall, in a deal ultimately valued at well over $200 million - and on the strength of a ten-episode test run alone - TBS bought 100 episodes of Perry's new half-hour "sit-dramedy," "House of Payne."

Perry bypassed the entire standard sitcom route - selling a show to a network, running a new episode every week, and hoping to stay on the air long enough to enter syndication, where the real money is - and did it his way. He put up $5 million to do the test episodes, maintained creative control, and, when TBS and others showed interest, made an incredibly lucrative deal that would allow him to have his show on up to five nights a week from the start. In the sitcom world, that's unheard of.

If there were any people left in Hollywood not paying attention to Perry up to that moment, they certainly all are now.

Not all the attention has been favorable. Some in the black community - academics, classically trained actors, the cultural elite - have criticized Perry's work for its representations of black people, calling him everything from moron to minstrel.

Perry knows he courts controversy by employing the conventions of what used to be called the "chitlin' circuit." But he's acutely aware that it's a particular audience - Christian, middle-class, African-American women - who turned him from a starving artist into an entertainment power. It's his ability to deliver that audience that makes him attractive to Lions Gate, TBS and his other partners.

Watching him in this house full of art he probably doesn't even like, in a town preoccupied with image, one can't help but wonder how long he can maintain that precious connection. After years of succeeding in relative obscurity, all but unknown to whites, Tyler Perry is poised to become a mainstream superstar. But will gaining white America's acceptance actually make - or break - him?

Humble beginnings

Perry grew up poor, the son of a carpenter who - as Perry puts it - "worked all his life, paying $116 a month for 30 years for this little house down in New Orleans." Seeing his father pay a mortgage on the cramped space he shared with his wife and four children - while others sold the houses he'd built them for far more than they'd paid him - young Perry decided that he wanted to be "the guy who owned the house." He developed an interest in architecture. (At age 12, comfortable with wood and already meticulous, he would draw additions for his father's clients, earning $30 or $40 a design.)

But there were challenges. Perry says he was physically abused by his father (they have since reconciled) and molested by a neighbor. And he lacked support: "Where I come from, you can have your dream, but keep it private. Don't share it with anybody, because they'll try to take it from you and snuff it out. That was the mentality of a lot of people I grew up around." Suffering depression, he attempted suicide twice.

Things changed when, at 21, he took his first road trip to Atlanta. "I thought I'd gotten to the Promised Land," he says. "I'd never seen black people doing so well. I'd always thought - because I tried to speak well and represent myself well, and that didn't go over too well with the fellas in the 'hood - that I was crazy. But when I got here and saw other people doing the same thing, I said, 'I'm home!'" He went back to New Orleans, packed his bags, and moved to Atlanta in 1990.

It was at the same time that he saw an episode of "Oprah" in which she said it was cathartic to write things down, so he began to chronicle stories from his life. In 1992, with the encouragement of friends and $12,000 in savings, those writings became his first stage play, "I Know I've Been Changed." Only 30 people attended the whole opening weekend. Perry was devastated - and broke.

So began a six-year stretch in which he went from job to job - as a bill collector and used-car salesman, among others - saving just enough to stage a play a year, only to see them all fail. At one point, evicted from his apartment and selling furniture to live, he spent more than a few nights in his Geo Metro convertible.

By 1998 he was ready to quit. He decided to stage one last show at Atlanta's House of Blues. This time he picked the most popular people from the city's most popular churches - choir members and pastors - and put them in the show. On a freezing opening night, with no heat at the venue and a nagging worry that he'd wasted his life, Perry looked out the window and saw a line reaching around the corner. He sold out eight nights at the House of Blues, followed by two more at the 4,500-seat Fox Theatre. He had found his audience.

Perry quickly became a force in urban theater, the circuit of venues that showed the raucous, faith-based, gospel-tinged plays. Artists like Duke Ellington, James Brown and Jimi Hendrix all found early homes on this circuit, and the form continues to flourish.

But these shows can lack the production values - and dramatic quality - of Broadway. The singing, not the acting, is often the focus. The story lines feature characters some critics find stereotypical - from the antebellum mammy to the modern deadbeat dad - and read more like morality tales than literature. More than anything, they show religious, working-class black people struggling with affliction - drug addiction, abandonment, poverty - and finding a way to laugh through it.

Perry delivered the same message, but with polished, scripted, ambitiously produced plays at major venues. Fans couldn't get enough. Soon Perry was doing 200 to 300 shows a year and playing to 30,000 people every week. He wasn't just producing the shows; he was writing, directing, starring, composing, doing everything from makeup to set design, and learning how to make it happen on a tight budget.

Hundreds of thousands of fans joined his e-mail list. They visited his Web site to buy DVDs and Perry paraphernalia, from soundtracks to keychains. And they loved him because he was like them, telling their stories of urban struggle with the same mix of humor and gravitas that they felt.

"And here we are $150 million later," he says, "from playing that little 200-seater to arenas 12,000, 20,000 strong. It's amazing."

Basking in success

Walking through his newly opened Tyler Perry Studios (TPS), the boss is still obsessed with the details. The 75,000-square-foot studio - which he drafted himself - features three sound stages, a 300-seat theater, editing facilities, prop and wardrobe departments and a gym.

A 15-minute tour of the building, which is still a work in progress, demonstrates that Perry's versatility extends beyond the stage. In a continuous and exhausting exchange with his contractor, he points out gaps in a door frame, orders extra wattage, adjusts the height of a garage door, realizes no bathroom was designed in a new section (and creates one), and fires - in absentia - the subcontractors doing the studio's floors and exterior doors. Problems solved.

TPS is the physical manifestation of Perry's multitasking, perfectionist mind. Perry and his producing partner, longtime Hollywood casting director Reuben Cannon, have their filming schedule mapped out through 2009. It includes three more films: "A Jazz Man's Blues," a period piece about the relationship between a jazz singer and a Holocaust survivor, in 2007; "Why Did I Get Married?" in 2008; and "Madea Goes to Jail" in 2009.

Perry is shooting a ten-episode television test of "Meet the Browns," another sit-dramedy based on one of his hit plays. That will be followed by a similar test for a series based on "Why Did I Get Married?" And all the while, Perry will be filming the 100 episodes of "Payne," which begins airing on TBS in June and on broadcast stations 15 months later.

If Perry's work continues to perform at this level, Tyler Perry Studios could well have done $1 billion in business by the end of 2009, making it a major independent studio. It's staggering, especially since just a few years ago, most people had never heard of Perry. But it's precisely because he is an outsider that he's been able to ignore so many industry standards, usually to his advantage.

"When you're on Tyler Perry time, you've got to get it right, whatever it takes, because he expects his vision to be implemented efficiently and instantaneously," says Roger Bobb, Perry's supervising producer, who, after filming the entire "Payne" test in 17 days, was surprised to find most sitcoms shoot one episode in an entire week. Evidently an episode a week doesn't work on Tyler Perry time. And neither does leaving your sitcom to the mercy of a network. Or waiting around for a studio to finance your film. (He put up cash to start filming "Diary" before there was even a studio attached.)

"Tyler Perry is a tornado," says Bobb, "but he's also like your brother, and you want him to succeed, so you just don't think about how impossible it all is. Because if you did, you'd have to stop."

Naysayers

Considering the scope of Perry's accomplishments, you might think that major studios would be breaking down his door. Surely he must be the toast of Hollywood - and of black America. That's all true, up to a point. And then it isn't true at all.

The studios "kind of look down on his work," says director John Singleton, who catapulted to fame with 1991's "Boyz n the Hood." "It's like they don't want to go there." Not only is Perry's art not high-brow - Madea, his signature character, has been known to carry a pistol and enjoy a joint or two - it's religious and often incredibly sad, and that just isn't how Hollywood wants to do funny black people.

It turns out that isn't how a lot of black people want to see themselves either. "In terms of getting an audience into the theater, yes, I give him success," says Ron Himes, founder of the St. Louis Black Repertory Company, who worries that Perry's and other touring plays are displacing traditional theater. "But in terms of developing an audience, I'm not as sure, because it's not necessarily a given that someone who's introduced to theater by a Tyler Perry play seeks out an August Wilson production for their next theater outing."

"It's a black anxiety," says Niyi Coker, a professor of theater and media studies at the University of Missouri. "We're afraid to let white America see us like this.... It's like saying, 'I don't want them to hear me singing the blues,' but it's okay now because they have accepted it. Why does it only have to be okay when they've okayed it? That is backward thinking."

Similarly backward is Hollywood's historical neglect of black audiences. "There was a trend to doing gimmicky black movies," says Michael Paseornek, Lions Gate's president of film production. "Put a few rappers in, put some songs in, deliver any old thing. Well, the audience stopped coming, but Tyler's brought them back."

Un-Hollywood

Perry is a walking reminder of how the industry's oversight could begin to be costly. And for Hollywood traditionalists and those served by the existing system, Perry's willingness to flout convention could set a worrisome precedent. "If you're Jerry Seinfeld or Ray Romano and you want to do a new project, why would you ever go through a traditional TV network again?" asks Turner Entertainment Networks president Steve Koonin. "The ability to go direct to consumer with a financing and marketing partner like TBS certainly outweighs the perils of having a 26-year-old cancel your show."

Perry is an obvious poster child for such a movement. "I haven't sold one thing, from day one - not one song, not one show, not one script - nothing," he says, "and I will not sell a thing. I want to leave all of this to my children."

As Matt Johnson, Perry's lawyer at entertainment firm Ziffren Brittenham, points out, Perry's been able to maintain that stance and still get groundbreaking deals because his partners know they're almost guaranteed a return on their investment. "So on the film side, he gets his cake because, like A-list folks - Tom Cruise, Tom Hanks, Will Smith - he gets significant first-dollar-gross participation," Johnson explains. "And he gets to eat it too by owning the copyright and receiving 50 percent of the true profit. And on the video side, he essentially gets 100 percent of the profits; we're just licensing the distribution rights to Lions Gate."

Don't think he beat it out of them, though. Perry's so loyal to Lions Gate that he actually told Paseornek to call him directly if he ever thought Perry's lawyers were taking advantage of the studio. Paseornek says he's had to use that card only once, but after he did, "five minutes later, we were closed." Definitely un-Hollywood.

One thing most people seem to agree on is Perry's impact. As an example, he's invaluable: "Tyler is willing to bet on himself," his William Morris agent, Charles King, says. "If more artists were to look at it from that perspective and think longer term - take less money or take no money on the front end, have an ownership position, have more creative control - they'd be more artistically fulfilled, and in the long run fare much better economically."

But will Perry change the industry? Unclear, says Paseornek, because he's seen what it takes to be Tyler Perry. "I don't know how you say that Tyler is anything but maybe the most unique person we've ever seen in our industry," he says, remembering a time when, while discussing song rights on the phone with Perry, he heard a crowd in the background and it dawned on him that Perry was moments from taking the stage. "To live through it with him, you realize it's unprecedented. He's Tyler Perry, and nobody else is."

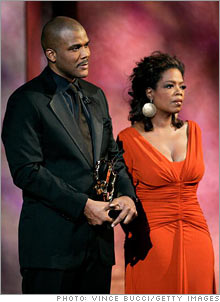

Sitting in his office at TPS, wearing his usual tracksuit and Nikes, Perry is the picture of relaxation. It isn't quite the suit and tie he put on for Oprah recently, but Oprah's teasing comment still applies: "You're looking very successful."

We sit down to our final talk, he at one end of his coffee table, me at the other. "It's all right, you can come sit over here," he says, pointing to a closer couch. I relocate and place my recorder on the table. He picks it up without a word and lays it on the arm of his chair. It's as though everything - me and my tools included - are part of one huge set for him.

That's just who he is, and he isn't about to give it up. "I don't think I'll ever be able to turn things over to somebody else because I'm very hands-on," he says. "I would love to have another Tyler Perry. If I could find somebody - if I could find my clone - man, I could really do some things, you know?" It remains to be seen how long he can keep up the energy to do it all by himself - particularly if he decides to do a network down the road, as he's said he might.

"I'll always serve the niche," Perry says, "because they are me. They held me up and walked me through and brought me to this point. But with each film, each play, we're trying to pull it a little higher, and we'll just keep stretching and see how far they're willing to go."

So has finally having the respect of white Hollywood changed Tyler Perry? A bit. He does, after all, have a small entourage now: At the moment it's his trainer, assistant, contractor and bodyguard. But it is without a doubt the most reluctant entourage anyone's ever seen; the trainer whispers eating directives as if it weren't his job, and Perry's given the bodyguard strict instructions not to "fall all over him" - otherwise known as the sole purpose of a bodyguard.

And that house in the Hills? "I hate all the furniture in it," he says, confessing that he rented everything from the previous owner. "But come back in three months, and it'll be totally different, a place where people can come in Hollywood and just have good, real conversations, without any pretenses."

In a town that's known for dashing dreams, Perry's been able to hold himself apart, succeeding enough to live in Hollywood without being of it. And rather than treat his blackness as a hindrance, he's brought a major piece of black culture with him - taking the chitlin' circuit from well-kept secret to mainstream stardom and using it to build an empire. There's no reason to believe that he's going to change for anyone. And for the time being, at least, it looks as though it's actually Tyler Perry who's changing Hollywood.

http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2007/02/19/8400222/index.htm |

Abm

"Cyniquian" Level Poster

Username: Abm

Post Number: 8376

Registered: 04-2004

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Thursday, February 15, 2007 - 07:25 am: |

|

Though I'm not much of an admirer of Tyler Perry the auteur I am a GREAT admirer of of Tyler Perry the ENTREPRENEUR. |

Brownbeauty123

Veteran Poster

Username: Brownbeauty123

Post Number: 1726

Registered: 03-2006

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Thursday, February 15, 2007 - 09:27 am: |

|

He seems gay to me. |

Tonya

AALBC .com Platinum Poster

Username: Tonya

Post Number: 4460

Registered: 07-2006

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Thursday, February 15, 2007 - 11:26 am: |

|

I'll admit that I’m biased. My mother, sister and I saw his play when he was in Philly and, when he came out on stage as himself for a final applause, I said to myself that boy is going to be a star, he was that brilliant. Plus I'm one of those folks who he gave something to talk about and laugh about and print on big T-shirts (I wore mine as a nightgown), long before he became a star. I think he's getting a bad rap by some critics only because he made a movie out of a play that was never made for The Big Screen. This cheapened it and made it look gaudy. On stage "Madea" was much better. I felt like I was given a front stage visual to the many stories about Black folk (my family included) that I've only heard being told. Both matched up perfectly, lol, and I had alot of fun; it was special. |

Cynique

"Cyniquian" Level Poster

Username: Cynique

Post Number: 7316

Registered: 01-2004

Rating:

Votes: 2 (Vote!) | | Posted on Thursday, February 15, 2007 - 04:52 pm: |

|

Tyler Perry is a sterling example of the success that can be achieved if you operate within the parameters of your own world. Racism didn't seem to be a concern of his. He identified a demograph in the black population and supplied what its members wanted, making a fortune in the process, turning himself into a capitalist supreme. I salute him because he did it all by himself; he is a one-man corporation, somebody who never had to worry about the "glass ceiling". |

A_womon

Veteran Poster

Username: A_womon

Post Number: 1393

Registered: 05-2004

Rating: N/A

Votes: 0 (Vote!) | | Posted on Sunday, March 11, 2007 - 11:27 am: |

|

Tyler Perry is my hero because he is a living example of how a black man can control his own destiny and succeed without having to get the white man's money or his stamp of approval on his projects or his life. I applaud him loudly and proudly!! If we had more Tyler Perrys maybe more black men would drop that sad tired excuse, "I can't do nothin or be nothin because the white man won't let me..." |

|